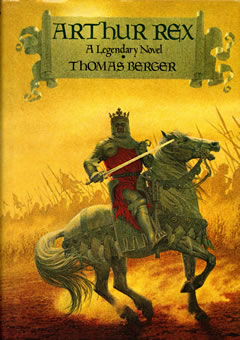

Arthur Rex: A Legendary Novel

You may click on the thumbnail images to view them full screen

Berger, Thomas. Arthur Rex: A Legendary Novel. New York: Delacorte Press/Seymour Lawrence, 1978.

American novelist Thomas Berger (1924-2014) attempts to tell the whole story of Arthur in Arthur Rex (1978). Berger demonstrates a great admiration for the legend of Arthur as told by Malory and others while he also modernizes, at times parodies, and radically revises the received version of the story. Like the legend itself, Berger's novel is full of paradoxes and ironies. For instance, after Arthur pulls the sword from the stone and assumes the throne, he quickly discovers the burden of kingship. One of the first of those discoveries is that a monarch has fewer liberties than his subjects do. He is 'Captive of many laws, ordinances, traditions, customs, and moreover, prophecies,' all of which conspire to guarantee that he 'is never free to do his will.'

Kingship reveals to Arthur other unpleasant realities, such as the fact that doing good may lead to evil. His marriage shatters in large part because of his own selfless actions. Arthur extols Launcelot's virtues to Guinevere and assigns Launcelot not to the quest, for which he longs, but to the queen's side as her protector and defender. The dissolution of Arthur's household mirrors the dissolution of his fabled Order, a noble concept that leads ultimately to war and to the deaths of every Knight of the Round Table. 'For this,' according to Berger, 'was the only time that a king had set out to rule on principles of absolute virtue, and to fight evil and to champion the good, and though it was not the first time that a king fell out with his followers, it was unique in happening not by wicked design but rather by the helpless accidents of fine men who meant well and who loved one another dearly.' But the renouncing of evil does not necessarily lead to good, as illustrated by the example of Sir Meliagrant. Enamored of Guinevere, whom he has detained and imprisoned, the notoriously wicked knight decides to change himself in order to win her affection. But 'whereas he had been fearsome when vile, he was but a booby when he did other than ill.' The newly-reformed Meliagrant is soon robbed and wounded by a beggar (who, insultingly, purchases the weapon he uses against Meliagrant with the gold that the knight had earlier given to him in charity) and then is killed in a fight with Launcelot. Before he dies, however, Meliagrant concedes—with some understatement—that 'This honor can be a taxing thing.'

Interestingly, Berger's female characters seem best able to articulate his notion of the pursuit of the dangerous ideal. Late in the novel, for instance, when Launcelot says that his war with Arthur is not the result of any hatred between the two, Guinevere thinks to herself, 'Nay, it hath happened because of men and their laws and their principles!' In effect, she implies that idealism itself is responsible for many of the world's problems. This notion is echoed by Morgan la Fey, Arthur's half-sister and his greatest nemesis. Throughout the novel, Morgan repeatedly seeks to undermine Arthur's kingdom. Finally, however, Morgan enters the Convent of the Little Sisters of Poverty and Pain, for after a long career in the service of evil she comes to believe that corruption 'were sooner brought amongst humankind by the forces of virtue, and from this moment on she was notable for her piety.'

Berger's use of the central theme of the dangerous ideal provides a means of exploring the great paradox of Malory's text, the destruction of a noble ideal largely through the flaws of noble men. It is a theme, perhaps the theme, of Arthur Rex that extreme adherence to moral rules can be more damaging than lapses in morality. This is not to suggest that Berger finds the desire to be better and to make things better wrong. But in Berger's novel, the desire to make things perfect without admitting human failings usually causes more trouble than outright imperfection does.