The Story of King Arthur and His Knights

You may click on the thumbnail images to view them full screen

Pyle, Howard. The Story of King Arthur and His Knights. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1903.

Howard Pyle (1853-1911), recognized as one of the greatest illustrators America has produced, was well known in his day as an illustrator of articles on American history for magazines such as Scribner's and Harper's, and he made his reputation as an illustrator and writer of children's books with his version of the story of Robin Hood (1883). Moreover, he was prolific, illustrating more than four hundred magazine articles or stories (nearly half of which he wrote himself), writing and illustrating more than twenty books, and contributing illustrations to more than a hundred books by other authors.

In four books that he wrote and illustrated—The Story of King Arthur and His Knights (1903), The Story of the Champions of the Round Table (1905), The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions (1907), and The Story of the Grail and the Passing of Arthur (1910)—Pyle retold the Arthurian stories from Arthur's birth to his death. Pyle was neither an editor nor even a reteller in the sense of one who merely simplifies an old story for young readers. Instead, Pyle created a new version of the legends, a version intended for children without patronizing them. He took the basic form from Malory but changed it to suit his purposes, combined material from other sources (the Mabinogion, French versions of the legends, and ballads), and added scenes and characters from his own imagination. He also used his own illustrations to complement the text.

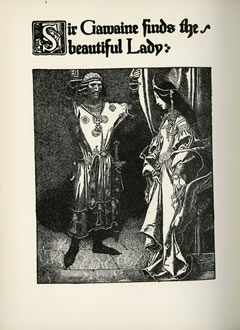

Pyle suggests that the knights of his stories provide models of behavior. Early in The Story of King Arthur, just after Arthur has drawn the sword from the anvil, Pyle writes: 'Thus Arthur achieved the adventure of the sword that day and entered into his birthright of royalty. Wherefore, may God grant His Grace unto you all that ye too may likewise succeed in your undertakings. For any man may be a king in that life in which he is placed if so he may draw forth the sword of success from out of the iron of circumstance. Wherefore when your time of assay cometh, I do hope it may be with you as it was with Arthur that day, and that ye too may achieve success with entire satisfaction unto yourself and to your great glory and perfect happiness.' The conclusion to the final adventure in The Story of King Arthur, a retelling of the story of Gawaine and the loathly lady, provides a similar link between the reader and the inhabitants of Camelot. When Gawaine marries the loathly lady, Pyle advises: 'when you shall have become entirely wedded unto your duty, then shall you become equally worthy with that good knight and gentleman Sir Gawaine; for it needs not that a man shall wear armor for to be a true knight, but only that he shall do his best endeavor with all patience and humility as it hath been ordained for him to do. Wherefore, when your time cometh unto you to display your knightness by assuming your duty, I do pray that you also may approve yourself as worthy as Sir Gawaine approved himself in this story.' In Pyle's retelling, especially in the first book in his tetralogy, Arthur and his knights are not ideals from another time and place for which there are no parallels in the modern world. Pyle uses them as exempla to demonstrate virtues that can be translated into the modern world by the reader in his or her personal life.

Howard Pyle trained a generation of artists who eventually became some of the most famous and prolific illustrators in America. Though he taught in various places, it was a summer location at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, on the Brandywine River that gave to his followers the name of the Brandywine School.